How Don Draper Lost His Way, and How to Find it Again

- POV’s

- October 7, 2019

- Brian Wieser

Key takeaways:

- Brand-focused companies and agencies were able to observably drive business outcomes with advertising in earlier (simpler) eras.

- Over time marketing functions were pushed deeper into organizational hierarchies and increasingly became a cost to be managed rather than a driver of growth.

- Marketers are best at balancing an understanding of what consumers will want with what is possible for a company to produce given all of the likely choices that competitors and supply chain partners make. Growth should improve when marketers are elevated within organizations.

In the pilot episode of the television series Mad Men, which takes place in 1960, Don Draper, creative director of Sterling Cooper, meets with the fictitious owner of cigarette brand Lucky Strike to discuss how to proceed with their advertising efforts. The interaction shown on screen – a company owner or CEO meeting with their agency to discuss a marketing issue in some depth – was presented as a seemingly everyday affair. Such meetings probably were relatively common in that era as television advertising was newly ascendant in the United States; the impact of a single commercial or slogan had clear impact. Through the 1950s, broadcast television signals did not reach the entire population, and companies who used the medium to advertise could observe plainly that a brand’s sales jumped meaningfully in geographies where television was available, relative to geographies where it was not.

Over the course of the following decades, many dominant brands had become ubiquitous and television access became universal, often diminishing the observable incremental impact of advertising on business outcomes. Meanwhile, many brand owners were consolidated into larger entities that pursued synergies and cost savings by centralizing operations related to product development, manufacturing, sales and different aspects of marketing. Many marketing tactics came to be standardized, mostly improved on the margins.

Meanwhile, managers at the top of many organizations dependent on the strength of their brands did not always have a full appreciation of how brand-building – and perhaps marketing by extension – works. At least many of those managers are by now self-aware: illustrating the problem, a new survey published earlier this year by the UK-based IPA and The Financial Times indicated that “over half of business leaders rate their knowledge of brand-building as average to very poor.”

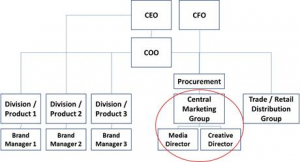

Marketers often sit in the middle of their organizations, removed from the top. By now, it is common that large companies have senior marketers who oversee what can be described as centers-of-excellence, responsible for functions such as consumer insights, relationships with external service providers agencies (including creative and media agencies) whose work is ultimately delivered to brand managers. But their role is often intended to support the application of best practices across brand managers’ business units rather than to lead them. Many of their activities are then heavily influenced by processes that procurement professionals deem necessary which, again, are focused more on cost management rather than the pursuit of growth. Few of those marketers report directly to the CEO of the company they work for, and many of their groups (perhaps the majority?) operate more as a cost center than anything else.

Organizationally, a large company’s reporting structure might look like this:

As for the agencies that work with brands, the individual client they most frequently interact with (the media director or creative director in our illustration here) may be far-removed from the brand owner, let alone the founder or CEO of the company that owns those brands. This can add another layer of complexity if the advice provided by agencies gets filtered on its way to ultimate decision-makers, a contrast with the Don Draper-Lucky Strike scenario.

In the above structure, it may be difficult to credit the marketing function or the agencies they work with for good outcomes, as brand owners or sales can be better positioned to take such credit – often appropriately so. Different approaches can be used to connect business results to marketing choices, but the outcomes following from related actions may be difficult to observe with the naked eye, leading to the use of attribution models that depend on a myriad of assumptions. Arguably, marketing that has meaningful long-term impact on a business should be observable without a model; however, if marketing is buried within a company it may be difficult for this function to drive the business choices that cause growth that everyone can plainly see.

And so we can have situations where companies that should want marketing to have the impact it had in Don Draper’s day possess an organizational structure that might limit it. Under these circumstances, what is a marketer – or an agency who wants to help them – to do?

Marketing is a function which can drive business growth and should sit at the top of every organization as well as the brand-focused divisions within them. Every company and business unit has the potential to realize rapid growth, if only they have the ability to organize their people and assets to enable it. Marketing is one of the best ways to drive this growth for a simple reason: marketers are the individuals who should best be able to balance an understanding of what consumers will want with what is possible for a company to produce given all of the likely choices that competitors and supply chain partners may make. A CEO or brand leader may very well be a marketer at heart and can provide a company or business unit with marketing leadership, but often CEOs’ and divisional leaders’ experiences are rooted in sales, finance or a company’s product development efforts. If those leaders are not marketing-oriented, they need to have a senior marketer who reports directly to them, even if marketing is a relatively small share of a company’s expenses (and for the average company, marketing typically represents a low-single digit share of those costs).

Whomever the most senior marketing-focused executive in a company is should then continue to oversee the centralized functions referenced above as they provide scale to the marketing activities performed by individual brands. Centralized data management on consumer insights and commercial activity from across a business should live under those individuals as well.

From there, companies should embed as much marketing knowledge, experience and budget-setting capabilities for marketing as high as possible within brand-owning business units and consider dual reporting into global marketing organization as well, with shared KPIs (key performance indicators) driving managers’ bonuses. Although challenging, matrixed reporting between brand-owners and marketing can help support the application of superior marketing capabilities to individual business units. The deeper marketers reside within individual business units and the closer it is to the top of business units, the more likely those individuals can lead growth rather than merely manage costs or operations.

Of course, significant structural changes only rarely and gradually occur. For a marketer whose structures are sub-optimal and unlikely to change, what can be done? Continue to make the case for the benefits that marketing leadership can bring. In general, marketers and the agencies who work with them can help audit the processes companies use to make decisions related to marketing and identify best practices that lead to growth from across a range of industries. Agencies will have clients with a range of growth profiles and should be able to identify the factors that are likely to support long-term commercial outcomes. At the same time, central marketing groups should be well-positioned to gather data from across a marketer’s organization and will at least be able to identify the elements of marketing that have been successfully applied internally. Both efforts can help produce benchmarks around which brands are most successful in accomplishing their goals within a company and across a range of different kinds of companies.

Driving changes such as those mentioned here aren’t necessarily easy to make happen, and of course there are always trade-offs to consider. They will likely be worthwhile. The Don Drapers of today’s world have a broader range of tools at their disposal than they did in the 1950s and 1960s to help companies grow. Ensuring that marketing sits at the top of corporate hierarchies will be key to ensuring they and their day-to-day counterparts once again